Introduction

This topic provides some background information on what EFL is and how it works. To start programming right away, see Getting Started with EFL UI Programming.

EFL is a collection of libraries that are independent or can build on top of each-other. They provide useful features that complement an OS’s existing environment, rather than wrap and abstract it, trying to be their own environment and OS in its entirety. This means that EFL expects you to use other system libraries and APIs in conjunction with EFL libraries to provide a whole working application or library - simply using EFL as a set of convenient pre-made libraries to accomplish a whole host of complex or painful tasks for you.

An important aspect of EFL is efficiency, both in speed and size:

- The core EFL libraries, even with Elementary, are about half the size of the equivalent “small stack” of GTK+ (used, for example, by GNOME), and about one quarter the size of Qt. Of course, with these kinds of numbers, you can always argue over what exactly constitutes an equivalent measurement.

- EFL is low on actual memory usage at runtime, with memory footprints a fraction the size of those in the GTK+ and Qt environments.

- EFL is fast, considering what it does. Some libraries claim to be very fast - but then, it is easy to be fast when you only handle simple and straightforward tasks. EFL is fast, while also tackling the more complex rendering problems involving, for example, alpha blending, interpolated scaling, and transforms with dithering.

The Tizen platform provides EFL as one of the native UI toolkit frameworks for developing a native application.

EFL Characteristics

EFL is aimed at not only desktop computers but also touch-screen and embedded devices, making EFL applications portable to many different types of devices. Applications do not need to care about the types of devices and profiles they run on. Instead of changing the code, it is typically enough to simply configure the applications for different devices.

The key characteristics of EFL include:

-

Fast performance

The main reason Tizen adopted EFL as its native toolkit is its speed. EFL is highly optimized by using a scene graph and retained-mode rendering. EFL is fast even in software rendering.

-

Small memory footprint

Despite its fast performance, EFL’s memory footprint is smaller than that of other toolkits with similar features. A small memory footprint is useful in the embedded world, since embedded devices do not normally have much memory.

-

Backend engine support

EFL supports several backend engines, such as X11 (OpenGL®, Xlib, Xcb), Wayland (OpenGL®, SHM), Direct Framebuffer, DRM, memory buffers, PS3 native, Windows®, and macOS. Applications do not need to deal with each backend engine separately.

-

GUI and logic separation

EFL supports a GUI layout (EDC) and logic separation by having the layout description in a plain text file and the logic code in the C or C++ source files.

-

Themeable

An EFL theme can be changed at runtime without restarting the application. UI components are customizable so that each application can create its own customized theme to overlay above the default theme, adding customized versions of UI components to achieve a specific look and feel.

-

Scalable

EFL supports a scale factor that affects the size of objects in the application at runtime. By configuring the scale factor, applications can scale up and down as needed. The scale factor also supports a default setting that allows applications to scale nicely out-of-the-box.

-

Animations

EFL supports different types of animations. Evas supports Evas maps with low-level APIs for performing 2D, 2.5D, and 3D object transformations. Edje supports predefined transitions and wrapping of Evas maps. Elementary supports transit APIs for various types of animations, which can be combined.

-

Hardware acceleration

EFL supports OpenGL® and OpenGL® ES acceleration.

Libraries in EFL

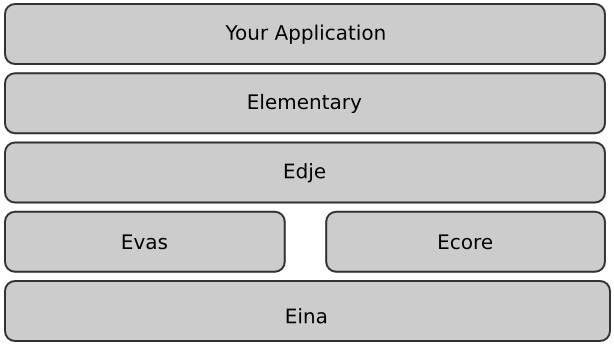

EFL is a collection of libraries. They cover a range of functionality from managing the application life-cycle to rendering graphical objects. EFL libraries build on top of each other in layers, steadily becoming higher-level, yet allowing access to each level as they go. The higher up you go, the less you have to do yourself. The Elementary library is about as high up as you get, while you still access layers below it for day-to-day tasks, as there is no need to wrap tasks that work perfectly well as-is.

Figure: EFL layers

Table: Libraries in EFL

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Elementary | Elementary (UI Components) is the topmost library with which you create your EFL application. It provides all the functions you need to create a window, create simple and complex layouts, manage the life-cycle of a view, and add UI components. The full list of UI components that can be used in Tizen can be found in Mobile UI Components and Wearable UI Components. |

| Edje | Edje is the library used by Elementary to provide a powerful theme. You can also use Edje to create your own objects and use them in your application, or even extend the default theme. For more information on Edje and the EDC format, see Layouting with EDC and Customizing UI Components. |

| Ecore | Ecore (Core loop and OS Interfacing) is the library that manages the main loop of your application. The main loop is one of the most important concepts you need to know about to develop an application. The main loop is where events are handled, and where you interact with the user through the callback mechanism. The main loop mechanisms are explained in Handling the Main Loop. |

| Evas | Evas (Primitive Graphical Objects) is the canvas engine. Evas is responsible for managing the drawing of your content. All graphical objects that you create are Evas objects. Evas handles the entire state of the window by filling the canvas with objects and manipulating their states. In contrast to other canvas libraries, such as Cairo, OpenGL®, and XRender, Evas is not a drawing library but a scene graph library that retains the state of all objects. The Evas concept is explained in Evas Rendering Concept and Method. Evas objects are created and then manipulated until they are no longer needed, at which point they are deleted. This allows you to work in the same terms that a designer thinks in: it is a direct mapping, as opposed to having to convert the concepts into drawing commands in the right order, and calculate minimum drawing calls needed to get the job done. |

| Eina | Eina is the basis of all the EFL libraries. Eina is a toolbox that implements an API for data types in an efficient way. It contains all the functions needed to create lists and hashes, manage shared strings, open shared libraries, and manage errors and memory pools. Eina concepts are explained in Data Types and Tools. |

In addition to the most important libraries explained above, the EFL includes other libraries, such as Eet, Embryo, and Emotion. Support for those libraries is planned in the future Tizen releases.

How EFL Works

EFL brings a few new or different paradigms to the table. Some of these mesh well with what is already done, while others are vastly different, but bring major benefits if understood and used correctly. One of the major paradigms is the rendering and canvas model that EFL has, thanks mostly to Evas, Ecore, and Edje. In order to understand it, you must first understand the general event and work flow model. Everything slots in nicely if this model is embraced (and extended appropriately).

EFL has embraced the same main loop concept that GTK+ and many other toolkits and software have adopted. It has rolled it wholeheartedly into the system as the core. The idea is that you do some initialization of the application and then enter a main loop function (in Ecore it is the ecore_mainloop_begin() function, or if you use Elementary, it wraps this with a shorter elm_run() function):

- This loop function sits in a loop and checks for events, handles timers and other services, and calls callbacks set up beforehand or during the running of the loop.

- The loop function exits if it has been requested to exit (in Ecore using the

ecore_main_loop_quit()function, and in Elementary that wraps Ecore using theelm_exit()function).

For those familiar with traditional game programming, this is familiar, except that you have also implemented the main loop with an infinite while or for loop that fetches input events, updates the game world, renders the updated scene, and then loops and repeats as quickly as it can.

In EFL, the main loop is not “dumb” and does not consume CPU resources unless there is work to do. It sleeps and consumes no CPU time until an event happens (except in rare circumstances, for example, when you use idlers that are called in a loop during what normally would be idle time waiting for something to happen). From EFL’s point of view, all of this is handled in Ecore, and it supports many constructs for manipulating the main loop in a logical and flexible way. EFL handles animation through animators, where the main loop handles timing out and scheduling these at regularly spaced intervals in time (on a best-effort basis), as with timers, pollers, idle enterers, idle exiters, idlers, jobs, fd handlers (file descriptor handlers) and event handlers.

In the EFL view, the application, when executing any callbacks other than idlers, is “active”. It goes in and out of this active state by calling the idle enterer and exiter callbacks (edge-triggered callbacks), which are triggered whenever going in and out of the idle state. Idlers themselves do not transition the main loop as such from being in an idle state, so any idler that needs to “wake up” the loop (to make the application conceptually active) needs to queue something that ordinarily wakes up the main loop, such as a job or timer. This is the only exception due to the conceptual model and the need for efficiency (not entering and exiting idle per idler call).

Besides the above exception, the loop model basically starts by calling the idle enterers, and then sleeps until something happens. What happens depends on the system, but wake-up events can be time-based (timers and animators) and these are scheduled by Ecore on a “best effort” basis. That means they use the system sleep mechanism (such as select() function with a timeout or epoll() function) to send the CPU to sleep and wait until an event on an input (a file descriptor) wakes up, or until the timeout happens.

The system can impose granularity limits on a sleep, so beware that this is not a guaranteed action, but in general good enough. Once Ecore wakes up, it finds out why it woke up and handles the situation appropriately. It calls timers or animators that expired, or calls fd handlers to read data (or write data) on “ready” fds and queue events as a result of this. Ecore also does some things that other main loops do not, such as serializing UNIX system handlers into the main loop event queue, so that things like SIGCHLD from child processes is handled for you with an event for the child exit placed in your event queue.

Rendering and Canvas

Evas and Edje live within the main loop model described above. Evas is the canvas engine that handles the entire “state” of a “window” (canvas) by filling that canvas with objects and manipulating their state. You can, for example, show, hide, move, and resize the objects, set the file sources for images, colors for rectangles, and fonts and text content for text.

When Evas renders, it evaluates the state of all objects and whether they have changed since the last rendering, and works out what to render and how to reflect the updated state of the canvas in the output. Evas attempts to minimize this update work, since it knows the prior and current state of every object, as well as knowing the entire canvas content:

- Evas can discard work well in advance as it knows that “later I cover up this rendering anyway”, and thus Evas can skip it.

- Evas defers as much work until the render time as it can, as at this point it considers the canvas state as “stable” and needing an update. This means that Evas can load fonts and images from the disk at the time it renders, to avoid repeated “create object, set image file, delete the object, create new one” cycles that can happen often during setup or major state changes. By deferring work as late as possible, Evas can avoid lots of “busy work” in doing useless tasks.

The work minimization allows the application using Evas to worry less about such optimizing and more about its logic flow, as the above “skip the work” optimizations are often done for you.

A major change caused by having such a canvas and state model for the GUI is that you no longer actually render anything yourself. You must change the mindset from a “I draw” to “I create and manipulate” model. This is very different from almost all lower and even mid-level APIs that developers are used to - everything from Xlib, Cairo, and GDI to OpenGL® and more. They all work on the “draw and forget” model, while Evas is a retained-mode scene graph that you manipulate.

Evas makes the cost of most operations (such as evas_object_move(), evas_object_resize(), and evas_object_show()) be “zero cost” (or as close to zero as possible). All most of these calls do is to update coordinates within an object and set a changed flag. That is it. They do not draw anything. For example, even setting the file on an image object through the evas_object_image_file_set() function only loads the image header, so the object can have the original image dimensions and alpha channel flag set. It does not decode the image data, avoiding a lot of file IO and decode overhead, and pushes this off until later (render time, if the image is visible and the data needed). If you are sure that you need the data though, Evas has the ability to begin an asynchronous preload of the image data in a background thread and inform you when it is ready.

If you mold your programming paradigm around this scene graph and state engine, you find yourself spending less time fighting EFL, and in fact end up with very lean, compact, and concise code that is almost entirely program and UI logic, which is what your application should be anyway, with all the nasty footwork being done for you. If you want to work with a more traditional model, where you have to take care of rendering yourself and you literally drive the timeline by hand, you find yourself fighting EFL and spending a lot of code and time working against optimizations and streamlining. Work with the model and your applications begin to be clean and seamless expressions of high-level logic, with the low-level handled for you by EFL in a clean and efficient way.

Related Information

- Dependencies

- Since Tizen 2.4